Measles is a highly infectious viral disease which can lead to serious complications such as pneumonia and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). Mumps can cause a wide range of complications, some very serious, including meningitis and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). Rubella (or German measles) is very dangerous for pregnant women because it can cause miscarriage or serious abnormalities in the unborn baby.

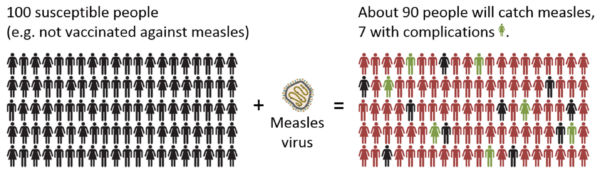

The MMRV vaccine should be given at 12 months of age and then again at 18 months of age. One vaccine results in over 90% protection for your child and having both vaccines means that it is almost impossible for your child to get measles. Unfortunately, as these vaccine preventable infections become less and less common, media coverage on vaccines increasingly focuses on their side effects and adverse reactions.

Although there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that the measles-containing vaccine is associated with an increased risk of autism, misinformation about this has directly resulted in unnecessary parental anxiety and a significant drop in MMR vaccine uptake. Unfortunately, we are now seeing an increasing number of cases of measles in the UK and across Europe. This has resulted in severe illness and even deaths in a number of adults and children.

Even if you think your child will be protected by herd immunity (other people being vaccinated around them), this is no longer the case because less than the required 95% of the population are being vaccinated. In addition, if your child was to travel to another country (even when they are an adult) or come into contact with someone with measles who is visiting from abroad, they will be completely unprotected and may contract the infection.

Unfortunately, measles is highly infectious and is spread by aerosolised particles and droplets coughed or sneezed by infected individuals.

Babies aged 6-12 months of age travelling to a country with high rates of circulating measles or to an area where there is a current measles outbreak, who are likely to be mixing with the local population, should receive a dose of MMRV vaccine before 12 months of age. This is because of the increased risk of severe measles disease in young children, including brain infection (SSPE). As the response to MMRV in infants is sub-optimal where the vaccine has been given before one year of age, immunisation with two further doses of MMRV should be given at the normal recommended ages.

Why should my child get the MMRV vaccine?

Measles is spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It can spread very easily. You can protect your child by making sure they get 2 doses of the MMR vaccine. Normally the 1st is given at 12 months and the 2nd at 18 months old. Even if you or your children have missed these vaccines, it’s not too late to get them. Contact your GP practice today. If your child has had both doses of their MMRV vaccine, there is very little chance of them getting unwell with measles (unless they have a severely weakened immune system).

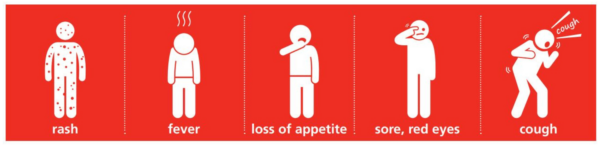

What are the symptoms of measles?

Measles starts with:

- fever

- red, sore, watery eyes (conjunctivitis)

- runny nose

- cough

After a few days:

- Small white spots may appear inside their mouth and on the back of their lips

- A rash. The rash starts on the face and behind the ears. It then spreads all over the body. The spots of the measles rash are sometimes raised and often join together to form blotchy patches. They are not usually itchy. The rash looks brown or red on white skin. It may be more difficult to see on brown or black skin.

What should you do if your child has symptoms?

- If you think your child has measles, let your GP practice know. You should inform them urgently if your child is under 12 months of age or has a severely weakened immune system.

- Measles usually starts to get better in about a week.

- To make your child more comfortable, you may want to lower their temperature using paracetamol (calpol) or ibuprofen. If you’ve given your child one of these medications and they’re still uncomfortable 2 hours later, you could try the other medication. If this works, you can alternate paracetamol and ibuprofen (every 2 to 3 hours), giving only 1 medicine at a time. Do not give more than the maximum daily dose of either medicine.

- However, remember that fever is a normal response that may help the body to fight infection. Paracetamol and ibuprofen will not get rid of it entirely. Paracetamol and Ibuprofen bring down the temperature but do not treat the infection. Whilst your child is unwell they will continue to get temperatures once the effects of the medicine has worn off.

- Avoid sponging your child. It doesn’t actually reduce your child’s temperature and may make your child shiver.

- Encourage your child to drink lots of fluids.

- If there are any crusts on your child’s eyes, gently clean them using cotton wool soaked in warm water.

- Your child can spread the infection to others from the time their symptoms start until about 4 days after the rash appears.

- Children cannot go back to school or nursery until 4 days after the rash has started. They should also avoid contact with babies, pregnant women, people who have not had 2 doses of the MMR or MMRV vaccine and people with weak immune systems.

- If you are pregnant and haven’t received 2 doses of the MMR or MMRV vaccine, or if there are any children in your family who have a severely weakened immune system or are under 12 months old, please inform your GP practice urgently. They might need immediate treatment to protect them from getting measles.

- If your child with measles has been in contact with someone who has a very weak immune system, let that person know about your child’s measles. Ask them to contact their GP practice or NHS 111 urgently.

- Finally, make sure that you and your partner are up to date with your MMR or MMRV vaccines before getting pregnant. Measles can be extremely severe during pregnancy and can harm your unborn baby.

My measles journey - read Saijal's story

Saijal Ladd, Prescribing Advisor – Medicines Planning and Operations, NHS North Central London ICB, shares her experience of contracting measles at 42, and the serious impact this had on her health.

Saijal Ladd, Prescribing Advisor – Medicines Planning and Operations, NHS North Central London ICB, shares her experience of contracting measles at 42, and the serious impact this had on her health.

Her story highlights the importance of getting vaccinated and serves as an important reminder that it’s never too late to catch up.

My measles journey

On 19 May 2016, I was admitted to Barnet General Hospital with measles.

I’d started to feel unwell a few days prior to this with a sore throat and temperature, but didn’t think it was anything serious so started a self-care routine of taking paracetamol and warm fluids with some rest.

However, despite taking medication my condition worsened, and my temperature remained high. On the night of 18 May, I felt really unwell with diarrhoea, fever and generalised weakness and by early the next morning I woke to find a rash all over my body.

Being a pharmacist, I knew this wasn’t a common cold or even flu and soon realised with all the other accompanying symptoms that the rash looked like measles.

I was feeling very unwell by now, so at around 7am I called 999. The ambulance crew arrived within an hour and after fully assessing my condition, transferred me to hospital. I was placed in isolation after being admitted, as by this point, I was vomiting as well.

My family were informed, but when they arrived, I was unable to speak to them as my voice had been affected by the vomiting!

By late afternoon, I’d been allocated a bed, but I don’t have much recollection of what happened after that as I was delirious and extremely drowsy from all the medication I was given. I was also started on fluids via a drip.

Later that night, some of my organs started to fail including liver, kidney and lungs. I woke up at some point to find an ICU consultant standing by my bedside assessing whether to admit me into intensive care.

I don’t recall what happened after this, but when I woke the next morning, I was still on the ward. A family member later told me how they nearly lost me during the night and that the clinicians were unsure if I would make it through until morning.

I was so grateful to have woken up and been told that I’d started to stabilise—it was now a waiting game to see if my body’s immune system would be able to fight against this virus. I also felt thankful for having led a fit and healthy life, as this allowed my body to fight the measles virus.

After a week in hospital, I was finally discharged.

My GP had to monitor me closely over the next few weeks however, and it took me about two to three months to get back to a normal activity level as my muscles had started to waste away due to lack of activity. I was unable to walk even a few metres without getting breathless and would sometimes wake up in the middle of the night feeling extremely weak due a drop in sugar levels.

This whole experience was extremely frightening, and I would urge all parents to consider vaccinating their children so that they don’t have to go through what I did in adulthood.

Looking back, I’m so grateful to be alive and really feel like life has given me a second chance!